|

The ties that bind

To repair a double-strand break, the ends of the broken strands must be

stripped of damaged or redundant bases, then brought together with a new

length of DNA. The new length may be assembled intact from a nearby "sister"

chromatid -- the adjacent arm of the chromosome -- or it may involve an

imperfectly matched length of DNA in a process called nonhomologous end-joining.

In both processes, the preparatory work on a broken strand is done by

a complex of two Mre11s and two Rad50s that form a "binding head."

The binding head is compact, but each of its Rad50s has a long tail,

extending up to 600 angstroms in mammals, which consists of a coil of

amino acids coiled back around itself -- like a twisted fiber pinched

in the middle, its two halves wound around each other to form a loose

piece of twine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

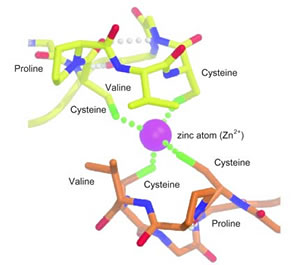

Rad50 tails link together when four

cysteine amino-acid residues in the CXXC motifs (two cysteines each,

in a pair of Rad50 tails) bind to a single, doubly ionized zinc atom.

|

|

At the pinch in the middle of the primary coil, where the tail bends

back on itself, there is a sequence of four amino acid residues similar

in all the organisms studied. The first and fourth residues in this sequence

are always cysteines, with various other residues in the second and third

places -- thus the label "CXXC motif."

Through x-ray crystallography the researchers learned that the CXXC motifs

were shaped like hooks, with the potential to grapple the tails of other

Rad50 proteins. Using laboratory techniques of gel filtration and ultracentrifugation,

the group confirmed that successful linkage of two Rad50 proteins depends

on the presence of zinc.

Chemical and structural studies showed that four cysteines (two each,

in a pair of Rad50 tails) bind to a single, doubly ionized zinc atom.

Discovery of this zinc-hook mechanism immediately suggested ways the Mre11

complex could connect DNA strands and bring them together.

A biological multitool kit

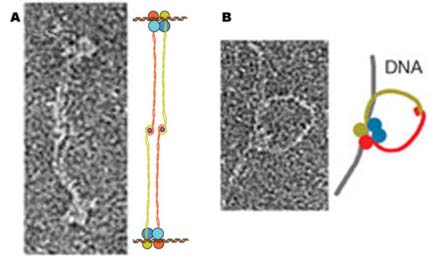

In a series of compelling electron micrographs of human and archaean Mre11

complexes, the researchers found several different conformations of linked

Rad50. Some pairs were joined by their tail hooks to form a bola shape,

with the binding heads of the Mre11 complex at both ends.

In one micrograph, the twin tails of a single binding head link to each

other, forming what looks like a finger ring, with the binding head as

its stone; an even more unusual micrograph shows a single-headed complex

of this kind actually bound to a length of DNA.

These conformations suggest distinct mechanisms by which linked Mre11

complexes can bridge sister chromatids or perform nonhomologous end-joining,

and how even a circular, single-headed Mre11 could bring together two

broken DNA ends.

|

|

| Electron micrographs show two possible

structures formed by Rad50 zinc hooks: (A) two Mre11/Rad50 complexes

could link their tails and attach to separate double strands of DNA

with their binding heads; (B) a single Mre11/Rad50 complex, its twin

tails linked in a circle, joins a broken double strand. |

| |

"Identification of the Rad50 zinc hook will allow us to understand

the mechanism for dynamic assembly and disassembly of the Mre11 complex,"

says Tainer, "which is critical for the repair of double-strand breaks

in DNA and thus for the avoidance of cancer-causing mutations."

The discovery is exciting not only for the questions it answers but for

the new questions it raises. Do binding heads begin their work separately,

thrashing their tails about until they grapple another bound complex that's

likely to help complete the repair? Do they link tails first and search

together for broken DNA to repair?

Other models are possible; which are correct and how the process works

in detail are yet to be determined, but other coordinating proteins and

interactions are likely to be involved. Thus finding the correct model

requires the complete NCI-funded team.

SBDR's leaders emphasize the cyclical nature of their work, first drawing

on genome sequencing and biochemical and genetic studies to suggest the

proteins most worth studying, then determining the structures of these

proteins through x-ray crystallography and other methods, in search of

understanding of how they work together to accomplish complex biological

tasks.

This knowledge, in turn, suggests biological experiments that can give

clues to the make-up and mechanisms underlying the complex machines that

mediate DNA repair, filling in more details of their intricate interactions

-- a new kind of research design cycle that provides a novel prototype

for productively linking structure and chemistry with biology.

Additional information:

|